|

Aging and Long-Term Care (10 Hours) > Chapter 3

|

|||||||||||||

Chapter 3: Psychological Aspects of AgingSince 1958, gerontologists have been following groups of older people in an ongoing study on aging---the Baltimore Longitudinal Study. They have discovered that our personalities stay pretty much the same over time. If a person is "a mean-spirited old codger," he or she was probably "a mean-spirited younger person"---age had nothing to do with it (Roush 2005); one just may be less inhibited about showing it as an older person. In fact, the "behavior of aging" may be a better phrase than the "psychological aspects of changing." Many new questions are being raised about how behavior is organized and how it changes over the course of life (Birren and Schaie 2005, xvii). Physical and social aspects of aging are both influences on psychological aspects of aging. An individual's interpretation of life and beliefs of control and values also have a vast influence on longevity and quality of life (Birren and Schaie 2005a). Although research indicates deterioration of cognitive processes (perception, memory, judgment, and reasoning) in aging, there is evidence that there is actually a significant resilience in these functions. In addition, well-learned, expertise-related mental processes do not decline; the ones that require great deliberation and effort are the ones that seem to decline universally. In addition to practice improving older-adult performance, it may also be improved by portrayal of a positive view of aging and memory. This suggests that motivation and emotion play significant roles in the cognitive lives of older people (Carstensen et al 2005, 355). There has also been found a link between personality and mortality. Earlier mortality is associated with low levels of conscientiousness and extroversion and high levels of neuroticism and negativity. Conversely, conscientiousness and positive outlooks on life are coupled with longer life. There appears to be a type of terminal personality decline in which change over a year or two in these constructs precedes death. (Mroczek et al 2005). To balance this out, older adults' own attitudes about aging can have an effect on their behavior, regardless of information from external sources. These attitudes can become more affirmative by emphasizing positive images of aging and suppressing the activation of negative attitudes (Hess 2005). The effectiveness of psychotherapy for older adults has been proven for several decades (Knight et al 2005, 418). Medicare and financial restraints may make it difficult for many older Americans to get this help. Changing Sense of SelfAccording to Birren, et al (2005a), there are several components of people's views of themselves. The real self is the person they believe themselves to be, including capacities, strengths, and weaknesses---"who I am." The ideal self is the person they would like to be, reflecting aspirations and goals---"who I want to be." The social image self is what they believe are the views other people have towards them---leading to "how well I believe I show who I am and who I want to be." Changes in Self-Awareness/PerceptionsWhen people err in self-evaluations, most of the time they overestimate their capabilities. This is good, because it enables one to take on more serious challenges and exert extra effort than if they underestimated their capabilities. Anxious and depressed people are actually more realistic in these evaluations. These folks are more likely to adapt to their situation, but they are less likely to try to change it (Cavanaugh and Green 1990). The extent to which one believes that outcomes are contingent on one's own behavior, and the extent that one evaluates his own ability to behave in such a way that outcomes are desirable have considerable influence on social, cognitive, and physical behavior. The first step in any conscious behavior change is the change in self-awareness (Vogelsang 2006). However, neurological research has proven that cultural and environmental learning creates lasting neurological structures, and that these structures are the foundation (and provide the limitations) for later learning and change. Under certain situations, these foundations may prevent much change in self-awareness and in self-directed change later on (Dittman-Kohli 2005, 333). For this reason, it may be difficult for an older person to make major changes, and even moderate changes may need psychotherapy in order to take place. Positive self-perceptions are theoretically viewed as signs of successful aging, age identity, and self-regulation processes. There is general agreement that positive self-perceptions of aging help in sustaining levels of social activity and engagement, enhance self-respect and well-being, and biophysiological functioning (Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al 2008). In a study on self-perceptions of aging ((Kleinspehn-Ammerlahn et al 2008), participants were asked at intervals over a period of six years what their felt age, physical age, and aging satisfaction were. Participants generally reported feeling and looking younger than they actually were, and showed relatively high levels of aging satisfaction over time. Over the six years the felt age remained the same, i.e., they always felt thirteen years younger on average. This seems to indicate the resilience of the older self, and the results of the study give a picture of the adaptive challenges faced by the aging self. However, there was decreased satisfaction with their own aging. Women apparently are less satisfied with their aging than men are, and they have a more accurate perception of their physical age. This study suggests that elderly with social loneliness, usually associated with poor health and/or the loss of significant others, may attribute it to aging and are discontented with their age-related changes. Interestingly, experimental literature suggests that priming and sense of "feeling younger" contributes to improvements in memory. All of this suggests that those working with the elderly can significantly help them by offering positive viewpoints and reinforcement. Life-Long and Age-Related Self-IdentitiesThere are several categories of identity issues relating to age:

Seniors use reminiscing to maintain the older identities. The experiences they recall give them information that they then use for self-interaction focused on past accomplishments. Carl Jung (1961, 320) believed that reminiscence is a search for symbolic meanings as an interior activity necessary for the ongoing elaboration of the self. Erikson (1950) believed that reminiscing affords opportunities for enhanced ego functioning mediated by past successes and failures. It makes it possible for individuals to reinterpret their history of experiences in order to make sense out of their present situations. How, then, do the elderly adopt new age-related identities? To what extent do they take them on? This concept requires the the elderly admit to the fact that they are old and willingly internalize that identity. Accepting this identity is apparently not related to negative stereotypes or to the loss of self-worth. Rather age identification primarily pertains to actual age-related deprivations (Ward 1977). It is generally known and accepted that all of our bodily functions decline as we age, usually not severe enough to be seriously debilitating until very old age. According to Biggs (1993, 36) the body serves as a means of assessing identity. There is also an inclination for age identification to be seen as positive when elderly people rate their situations---health and otherwise---as fortunate compared with those of other elderly people with whom they interact. Self-Worth (or Self-Esteem) with AgingSelf-worth, or self-esteem, is the way in which individuals assess their own worth to themselves and to others. It has to do with whether older people sustain a sense of personal worth when they suffer the many physical, social, and mental losses generally associated with old age. Self-worth is regularly found to be high among the aged. In fact, one study (Atchley 1991, 104-5) found that self-worth was almost twice as high among elderly as among teen-agers. Reminiscing again seems to play a part in this, as seniors remember past accomplishments---an important source of feelings of contentment and a sense of integrity (Brown 1996). With the advent of senior centers, social networks appear to be increasing among the elderly. These become a source of new forms of self-worth. Brown (1996, 76) sums it up: "The basically positive nature of social-psychological well-being of elderly people today can be largely attributed to their patterns of interaction. Particularly important is the fact that they increasingly prefer and choose age-peer interaction. Interaction among those in common situations, such as retirement and old age, is a dynamic process that inevitably produces new self-perceptions, new roles, and new relationships that are appropriate and directly applicable to those common situations. To ignore those very dynamic processes in analyzing the social psychology of aging is to misunderstand what becoming old today is really like." Coping and Adjustments"Coping is a crucial variable influencing the adaptational outcomes of a person's struggle to get along or live well" (Lazarus and DeLongis 1983, 248). Lazarus and DeLongis define two coping strategies:

[QN.No.#33.Which of the following is associated with problem-focused coping?] Pearlin and Schooler (1978) classify three general divisions of coping, the first of which conforms with problem-focused coping, and the second and third of which might be sub-topics of emotion-focused coping: 1. Responses that modify situations 1. Responses that are used to reappraise the meaning of problems 2. Responses that help individuals manage tension Kart and Kinney (2001) advise that not all coping strategies are necessarily adaptive. For example, in the news there have been stories of folks that have coped using murder/suicide strategies. They obviously have not engaged in adaptive problem-focused coping. An elderly person who copes with the death of a spouse by drinking to excess is engaging in an emotion-focused coping strategy that is not adaptive. [QN.No.#34.All coping strategies are adaptive.True or False] Many have considered stress and coping to be isomorphic, and the expression stress management has all but replaced coping in professional literature. It is unlikely that researchers can arrive at generalized principles of coping, because personality and motivational variables---such as life goals---are critical in the choices of coping strategies. Aging is associated with social losses, ill health, and various declining perceptual, motor, and cognitive abilities. Coping is therefore of great importance in the analysis of the life of an older person. (Furchtgott and Furchtgott 1999). "…Whether we view people in the context of the entire life course or more narrowly in the context of aging, we must see them as engaged in a life drama with a continuous story line that is best grasped not as a still photo but as a moving picture with a beginning, middle, and end" (Lazarus and DeLongis 1983, 253). Coping MechanismsPeople respond to life changes and stress with different coping mechanisms. Common negative coping mechanisms are:

[QN.No.#35.Which of the following coping mechanisms are positive ones?] More profitable coping processes are those in which an individual:

Adjustment to Change and LossIndividuals work all of their lives to gain or exercise many things: health, relationships, talents and abilities, status, and independence. Growing older inevitably results in the loss of many of these. Hayslip (1995) distinguishes between primary and secondary losses:

One coping mechanism that can be taught to an elderly client is an appropriate relaxation technique, such as (McAndrew 2002, 218ff):

Social workers and home care providers must pay attention to psychologic dynamics in order to help a client face these losses that accompany growing older with integrity rather than despair (Davidhizar and Shearer 1999). Environment Often the loss of one's independence---or sometimes the decline in income or earning power---results in a change of environment. This can be moving into a new home---smaller, less convenient, or to a managed care or nursing home. When the move is determine by need or circumstance rather than by choice, the adjustment will be doubly difficult. A change in environment exposes elderly individuals to a large number of new stimuli at a time of life when they have an aging and decreasingly-effective stress-control response. A change in location often results in increased vulnerability to or occurrence of disease; mental disorientation may also result. Health professionals know well of the independently functional elder person who cannot perform simple activities of daily living when admitted to a nursing home (McAndrew 2002, 210). One step that can help reduce the stress of a change of environment due to need or circumstance is to consult and prepare them; taking it for granted that the elderly will adjust causes extra frustration and possible confrontation (Eren 2007). Other steps that may be taken are (Kane et al 2004, 129):

Role Transitions There are a number of role changes that occur with aging. The work role and the role of spouse or partner are changes that most elderly expect. And those are roles for which there is usually a lot of support if one wants that. To the extent that an event is understood as being expected and happening at the right time, a role transition may be comfortable and even gladly received. If a person must retire "too early" or is widowed "too soon," the person will have more difficulty making the transition than if it happened at a more expected time (Ebersole et al 2005). Role transition is momentous kind of change because it powerfully influences the behavior and social identity of each person that is part of the process (Allen and van de Vliert 1984). Even when the role shift is a desired one and ideal conditions abound, there is a significant amount of stress or strain (Minkler and Biller 1979, 13). Being stressed by role transitions can produce reactions in all levels of the individual's functions: affective, perceptual/cognitive, and behavioral (French and Kahn 1962). At the level of affect, there is widespread involvement of the autonomic nervous system that accompanies emotional reaction. The individual will experience this as agitation, which can cause a variety of emotional reactions such as depression, anxiety, or anger, as the person tries to adjust to the stress. At the perceptual/cognitive level, the individual may react by selective monitoring of the environment, reinterpreting events, or redeploying attention. At the behavioral level, the person may do nothing or may find means to potentially reduce the stress. These reactions can have long- or short-term outcomes. For example, using tranquilizers will bring only temporary relief, but establishing a strong social support network could have long-term results. (Allen and van de Vliert 1984, 14-5). Direct the elderly in-transition clients into activities---yet allowing time for reflection---such as:

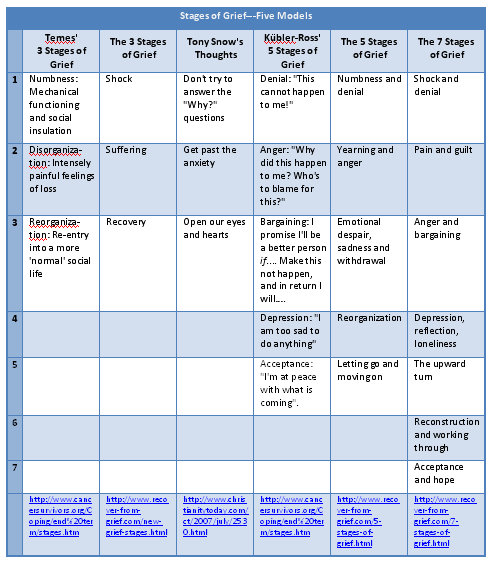

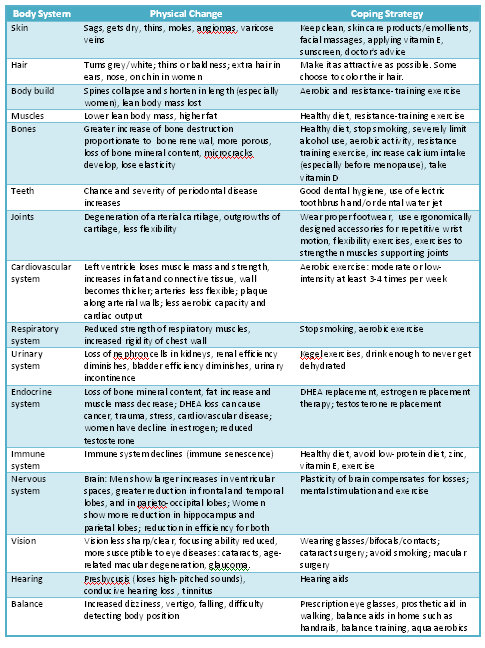

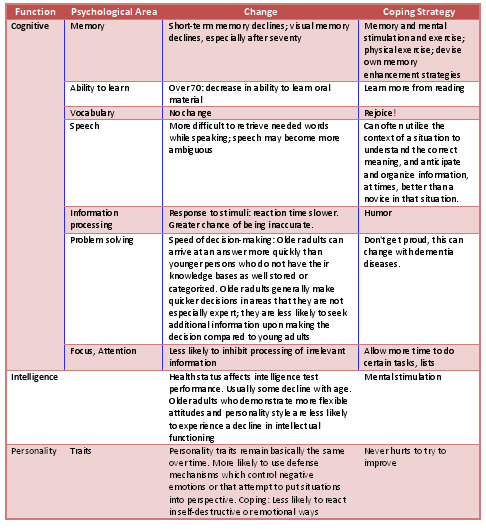

Newly Widowed or Divorced In March 2000, the Census Bureau estimated that 44.9% of women over 65 were widowed and that 14% of men in that age bracket were widowers. That is about 1.1 million seniors that have lost their spouses (Spraggins 2000). Widows and widowers have different challenges in their widowhood. Both report being lonely; widows report more anxiety about finances, whereas widowers' concerns are regarding household tasks. Social workers need to be prepared to help them in those areas of worry. No matter the topics of concern, both experience grief for their bereavement. There have been many attempts to define grief, and particular stages of grief have been identified. None of the "stages" are meant to be taken as a rigid framework that applies to everyone that grieves. Rather they are meant to indicate what feelings a person may experience---but they may not; even if they experience all of those in a particular list of stages, they may not experience them in that order, or they may wobble back and forth between some of them. But if a client is feeling one of the "stages," it often comforts or encourages them to know that what they are feeling is normal. Even Kbler-Ross (1975), who defined the first "Five Stages of Grief" many years ago, is reported to have said of them, "They were never meant to help tuck messy emotions into neat packages. They are responses to loss that many people have, but there is not a typical response to loss, as there is no typical loss. Our grieving is as individual as our lives” (Smith et al 2009). Here is a chart of five models of grief stages. Use them to help.  Coping with Age-Related Physical ChangesAttention has been paid to some of the physical changes that occur with age. Now we want to focus on how the elderly can cope with some of those changes. "Age-related physical changes may have psychological and social implications. Biological changes can affect the individual’s attitudes, behaviors, and identity as self-perception is affected by one’s appearance and competence" (Eddington and Shuman 2006, 7). The following chart gives specific changes and coping strategies for them (info from Eddington and Shuman 2006).  Coping with Age-Related Psychological ChangesThe ability to adapt to everyday life may be influenced by the effects of aging on mental abilities. Cognitive abilities may also affect self-respect and how individuals view their own aging process. However, normal age-related changes are not all negative, in spite of some losses in speed and memory in later years. Elderly people can compensate for memory changes by devising a balanced attitude in their self-concept (Eddington and  The person who is going to imminently lose his or her life grieves as much or more than one who has lost a loved one. They will also likely go through one or more of the states of grief. Kbler-Ross (1975, 160) found that "people who deny less and are more able to move through the five stages after they discover that they have a terminal illness are those people who (1) are willing to converse in depth with significant others about what their present experience is like, (2) meet others on equal terms, that is, are able to enter into real dialogue with others where both can share what is "real" with the other, and (3) accept the good with the bad." These three aspects closely align with Allport's (1950) three attributes of the mature personality, which are described several ways:

Tony Snow (2007), President George W. Bush's press secretary who quit because he was dying of cancer, gave three thoughts: 1. We shouldn't spend too much time trying to answer the why questions: Why me? Why must people suffer? Why can't someone else get sick? 2. We need to get past the anxiety 3. We can open our eyes and hearts Whatever route the dying elderly seems to need, the social worker must be reverent towards the person's religious views and also be willing to aid them through the more negative stages of grief if they are open to that. Counter Transference Issues in Working with the ElderlyWorking with the elderly can be an emotionally draining experience. As a result of the different issues that the elderly are dealing with, often times they may lash out at the therapist or social worker because they are conveniently present, or because they feel it is safe to do so. Sometimes there is a lot of complaining about situations out of the therapist's control, whether it be present circumstances, family relationships or even paranoia causing the client to have suspicion of everyone around them. The helper who becomes too emotionally involved or wants to be always pleasing can be taken for an emotional roller coaster and get "burned out." In addition, the helper may have a relationship with a family member who is elderly, whether a parent, grandparents, or others close to them. The helper must maintain an awareness of feelings that might be brought into the therapeutic relationship. Another emotional experience for the therapist or social worker working with the elderly is when a client passes away, either abruptly or resulting from a known terminal illness. This can be both challenging and emotionally draining, but with a proper balance, can bring a great deal of satisfaction. "Being with them" during times of grief and supporting the expression of feelings while also working with their families can be a very difficult, but uplifting experience when the client and their loved ones are able to move through the grief, and find acceptance and peace. Again, it can be difficult for the practitioner to engage and support the client and their family through the processes, while managing personal emotions. Not every process will go well. In fact, if they are seeing a therapist, chances are there will be quite a roller coaster of emotions. |

|

||||||||||||

|

Aging and Long-Term Care (10 Hours) > Chapter 3

Page Last Modified On:

Deprecated: Function strftime() is deprecated in /home/devxspeedy/public_html/lib/smarty-3.1.34/libs/plugins/modifier.date_format.php on line 81 April 18, 2015, 11:21 AM |

|||||||||||||