|

HIV / AIDS Course > Chapter 3 - HIV Prevention

|

|

Chapter 3: HIV PreventionA. Using HIV Medication to Reduce Risk1. HIV Treatment as PreventionTreatment as prevention (TasP) refers to taking HIV medication to prevent the sexual transmission of HIV. It is one of the highly effective options for preventing HIV transmission. People living with HIV who take HIV medication daily as prescribed and get and keep an undetectable viral load have effectively no risk of sexually transmitting HIV to their HIV-negative partners. TasP works when a person living with HIV takes HIV medication exactly as prescribed and has regular follow-up care, including regular viral load tests to ensure their viral load stays undetectable. Taking HIV Medication to Stay Healthy and Prevent Transmission If you have HIV, it is important to start treatment with HIV medication (called antiretroviral therapy or ART) as soon as possible after your diagnosis. If taken every day, exactly as prescribed, HIV medication can reduce the amount of HIV in your blood (also called the viral load) to a very low level. This is called viral suppression. It is called viral suppression because HIV medication prevents the virus from growing in your body and keeps the virus very low or “suppressed.” Viral suppression helps keep you healthy and prevents illness. If your viral load is so low that it doesn't show up in a standard lab test, this is called having an undetectable viral load. People living with HIV can get and keep an undetectable viral load by taking HIV medication every day, exactly as prescribed. Almost everyone who takes HIV medication daily as prescribed can achieve an undetectable viral load, usually within 6 months after starting treatment. There are important health benefits to getting the viral load as low as possible. People living with HIV who know their status, take HIV medication daily as prescribed, and get and keep an undetectable viral load can live long, healthy lives. There is also a major prevention benefit. People living with HIV who take HIV medication daily as prescribed and get and keep an undetectable viral load have effectively no risk of sexually transmitting HIV to their HIV-negative partners. Learn more: Read our fact sheet about the health and prevention benefits of viral suppression and maintaining an undetectable viral load (PDF 166 KB). Keep Taking Your HIV Medication to Stay UndetectableHIV is still in your body when your viral load is suppressed, even when it is undetectable. So, you need to keep taking your HIV medication daily as prescribed. When your viral load stays undetectable, you have effectively no risk of transmitting HIV to an HIV-negative partner through sex. If you stop taking HIV medication, your viral load will quickly go back up. If you have stopped taking your HIV medication or are having trouble taking all the doses as prescribed, talk to your health care provider as soon as possible. Your provider can help you get back on track and discuss the best strategies to prevent transmitting HIV through sex while you get your viral load undetectable again. How Do We Know Treatment as Prevention Works?Large research studies with newer HIV medications have shown that treatment is prevention. These studies monitored thousands of male-female and male-male couples in which one partner has HIV and the other does not over several years. No HIV transmissions were observed when the HIV-positive partner was virally suppressed. This means that if you keep your viral load undetectable, there is effectively no risk of transmitting HIV to someone you have vaginal, anal, or oral sex with. Read about the scientific evidence. Talk with Your HIV Health Care Provider Talk with your health care provider about the benefits of HIV treatment and which HIV medication is right for you. Discuss how frequently you should get your viral load tested to make sure it remains undetectable. If your lab results show that the virus is detectable or if you are having trouble taking every dose of your medication, you can still protect your HIV-negative partner by using other methods of preventing sexual transmission of HIV such as condoms, safer sex practices, and/or pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for an HIV-negative partner until your viral load is undetectable again. Taking HIV medicine to maintain an undetectable viral load does not protect you or your partner from getting other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), so talk to your provider about ways to prevent other STDs. Talk to Your PartnerTasP can be used alone or in conjunction with other prevention strategies. Talk about your HIV status with your sexual partners and decide together which prevention methods you will use. Some states have laws that require you to tell your sexual partner that you have HIV in certain circumstances. Other Prevention Benefits of HIV Treatment In addition to preventing sexual transmission of HIV there are other benefits of taking HIV medication to achieve and maintain an undetectable viral load:

2.Pre-exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP) On October 3rd, 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved a second drug for pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) as part of ongoing efforts to end the HIV epidemic.

The content of this page (https://www.hiv.gov/hiv-basics/hiv-prevention/using-hiv-medication-to-reduce-risk/pre-exposure-prophylaxis) is being revised. What is PrEP? PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis, is an HIV prevention method in which people who don't have HIV take HIV medicine daily to reduce their risk of getting HIV if they are exposed to the virus. Currently, the only FDA-approved medication for PrEP is a combination of two anti-HIV drugs, emtricitabine and tenofovir disoproxil fumarate, sold in a single pill under the brand name Truvada™. PrEP can stop HIV from taking hold and spreading throughout your body. >br/>It is prescribed to HIV-negative adults and adolescents who are at high risk for getting HIV through sex or injection drug use. Why Take PrEP? PrEP is highly effective when taken as indicated. The once-daily pill reduces the risk of getting HIV from sex by more than 90%. Among people who inject drugs, it reduces the risk by more than 70%. Your risk of getting HIV from sex can be even lower if you combine PrEP with condoms and other prevention methods. Is PrEP Right for You? PrEP may benefit you if you are HIV-negative and ANY of the following apply to you: You are a gay/bisexual man and you:

Is PrEP Safe? No significant health effects have been seen in people who are HIV-negative and have taken PrEP for up to 5 years. Some people taking PrEP may have side effects, like nausea, but these side effects are usually not serious and go away over time. If you are taking PrEP, tell your health care provider if you have any side effect that bothers you or that does not go away. And be aware: PrEP protects you against HIV but not against other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) or other types of infections. Combining PrEP with condoms will reduce your risk of getting other STIs. How Do You Get PrEP?  If you think PrEP may be right for you, visit your doctor or health care provider. PrEP is only available by preblockedion. Because PrEP is for people who are HIV-negative, you'll have to get an HIV test before starting PrEP and you may need to get other tests to make sure it's safe for you to use PrEP. If you take PrEP, you'll need to see your provider every 3 months for repeat HIV tests, preblockedion refills, and follow-up. Many health insurance plans cover the cost of PrEP. A commercial medication assistance program is available for people who may need help paying for PrEP. Learn More About PrEP If you think PrEP might be right for you, or you want to learn more visit CDC's PrEP Basics. 3. Post-Exposure ProphylaxisWhat Is PEP?

PEP, or post-exposure prophylaxis, is a short course of HIV medicines taken very soon after a possible exposure to HIV to prevent the virus from taking hold in your body. You must start it within 72 hours after you were exposed to HIV, or it won't work. Every hour counts. PEP should be used only in emergency situations. It is not meant for regular use by people who may be exposed to HIV frequently. How Do I Know If I Need PEP? If you are HIV-negative and you think you may have been recently exposed to HIV, contact your health care provider immediately or go to an emergency room right away. You may be prescribed PEP if you are HIV-negative or don't know your HIV status, and in the last 72 hours you: On 5/5/18, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) alerted the public that serious cases of neural tube birth defects have been reported in babies born to women with HIV who were treated with the drug dolutegravir prior to conception. The CDC has issued an interim statement on the implications for PEP. Talk to your health care professional.

Your health care provider or emergency room doctor will evaluate you and help you decide whether PEP is right for you. In addition, if you are a health care worker, you may be prescribed PEP after a possible exposure to HIV at work, such as from a needlestick injury. How Long Do I Need to Take PEP? If you are prescribed PEP, you will need to take the HIV medicines every day for 28 days. You will also need to return to your health care provider at certain times while taking PEP and after you finish taking it for HIV testing and other tests. How Well Does PEP Work? PEP is effective in preventing HIV infection when it's taken correctly, but it's not 100% effective. The sooner you start PEP after a possible HIV exposure, the better. While taking PEP, it's important to keep using other HIV prevention methods, such as using condoms the right way every time you have sex and using only new, sterile needles and works when injecting drugs. Does PEP Cause Side Effects? The HIV medicines used for PEP may cause side effects in some people. These side effects can be treated and aren't life-threatening. If you are taking PEP, talk to your health care provider if you have any side effect that bothers you or that does not go away. PEP medicines may also interact with other medicines that a person is taking (called a drug interaction). For this reason, it's important to tell your health care provider about any other medicines that you take. Can I Take PEP Every Time I Have Unprotected Sex? No. PEP should be used only in emergency situations. It is not intended to replace regular use of other HIV prevention methods. If you feel that you might be exposed to HIV frequently, talk to your health care professional about PrEP. How Can I Pay for PEP?

Content Source: HIV.gov Date last updated: June 26, 2019 B. Reducing Sexual Risk1. Preventing Sexual Transmission of HIVThere are several ways to prevent getting or transmitting HIV through sex.

If you are HIV negative, you can use HIV prevention medications known as pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) or post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) to protect yourself. You can also use other HIV prevention methods, below. If you are living with HIV, the most important thing you can do to prevent transmission and stay healthy is to take your HIV medication (known as antiretroviral therapy or ART), every day, exactly as prescribed. People living with HIV who take HIV medication daily as prescribed and get and keep an undetectable viral load have effectively no risk of sexually transmitting HIV to their HIV-negative partners. There also are other options to choose from, below. How Can You Prevent Getting HIV from Anal or Vaginal Sex? If you are HIV-negative, you have several options for protecting yourself from HIV. The more of these actions you take, the safer you can be. You can:

Is Abstinence an Effective Way to Prevent HIV? Yes. Abstinence means not having oral, vaginal, or anal sex. An abstinent person is someone who's never had sex or someone who's had sex but has decided not to continue having sex for some period of time. Abstinence is the only 100% effective way to prevent HIV, other sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and pregnancy. The longer you wait to start having oral, vaginal, or anal sex, the fewer sexual partners you are likely to have in your lifetime. Having fewer partners lowers your chances of having sex with someone who has HIV or another STD. If You Are Living with HIV, How Can You Prevent Passing It to Others? If you are living with HIV, there are many actions you can take to prevent transmitting HIV to an HIV-negative partner. The more of these actions you take, the safer you can be.

Also, encourage your partners who are HIV-negative to get tested for HIV so they are sure about their status and can take action to keep themselves healthy. Use HIV.gov's HIV Testing Sites & Care Services Locator to find a testing site nearby. Content Source: HIV.gov Date last updated: October 12, 2018 C. Reducing Risk from Alcohol and Drug Use1. Alcohol and HIV RiskDrinking alcohol, particularly binge drinking, affects your brain, making it hard to think clearly. When you're drunk, you may be more likely to make poor decisions that put you at risk for getting or transmitting HIV, such as having sex without a condom. You also may be more likely to have a harder time using a condom the right way every time you have sex, have more sexual partners, or use other drugs. Those behaviors can increase your risk of exposure to HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Or, if you have HIV, they can also increase your risk of transmitting HIV to others.

What Can You Do? If you drink alcohol:

Need help?

Staying Healthy If you are living with HIV, alcohol use can be harmful to your brain and body and affect your ability to stick to your HIV treatment. Learn about the health effects of alcohol and other drug use and how to access alcohol treatment programs if you need them. Content Source: HIV.gov Date last updated: August 27, 2018 2. Substance Use and HIV Risk How Can Using Drugs Put Me at Risk for Getting or Transmitting HIV?

Using drugs affects your brain, alters your judgment, and lowers your inhibitions. When you're high, you may be more likely to make poor decisions that put you at risk for getting or transmitting HIV, such as having sex without a condom, have a hard time using a condom the right way every time you have sex, have more sexual partners, or use other drugs. These behaviors can increase your risk of exposure to HIV and other sexually transmitted diseases. Or, if you have HIV, they can increase your risk of spreading HIV to others. And if you inject drugs, you are at risk for getting or transmitting HIV and hepatitis B and C if you share needles or equipment (or "works") used to prepare drugs, like cotton, cookers, and water. This is because the needles or works may have blood in them, and blood can carry HIV. You should not share needles or works for injecting silicone, hormones, or steroids for the same reason. Here are some commonly used substances and their link to HIV risk:

How Can You Prevent Getting or Transmitting HIV from Injection Drug Use? Your risk is high for getting or transmitting HIV and hepatitis B and C if you share needles or equipment (or "works") used to prepare drugs, like cotton, cookers, and water. This is because the needles or works may have blood in them, and blood can carry HIV. If you inject drugs, you are also at risk of getting HIV (and other sexually transmitted diseases) because you may be more likely to take risks with sex when you are high. The best way to lower your chances of getting HIV is to stop injecting drugs. You may need help to stop or cut down using drugs, but there are many resources available to help you. To find a substance abuse treatment center near you, visit SAMHSA's treatment locator or call 1-800-662-HELP (4357). If you keep injecting drugs, here are some ways to lower your risk for getting HIV and other infections:

What Are Syringe Services Programs? Many communities have syringe services programs, also called syringe exchange programs or needle exchange programs. SSPs are places where injection drug users can get new needles and works, along with other services such as help with stopping substance abuse; testing and, if needed, linkage to treatment for HIV, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C; and education on what to do for an overdose. SSPs have been demonstrated to be an effective component of a comprehensive approach to prevent HIV and viral hepatitis among people who inject drugs, while not increasing illegal drug use.Find one near you. Staying Healthy If you are living with HIV, substance use can be harmful to your brain and body and affect your ability to stick to your HIV treatment regimen. Learn about the health effects of alcohol and other substance use and how to access substance abuse treatment programs if you need them. Content Source: HIV.gov Date last updated: August 27, 2018 D. Reducing Mother-to-Child Risk1. Preventing Mother-to-Child Transmission of HIVAn HIV-positive mother can transmit HIV to her baby in during pregnancy, childbirth (also called labor and delivery), or breastfeeding.

If you are a woman living with HIV and you are pregnant, treatment with a combination of HIV medicines (called antiretroviral therapy or ART) can prevent transmission of HIV to your baby and protect your health. How Can You Prevent Giving HIV to Your Baby? Women who are pregnant or are planning a pregnancy should get tested for HIV as early as possible. If you have HIV, the most important thing you can do is to take ART every day, exactly as prescribed. If you're pregnant, talk to your health care provider about getting tested for HIV and how to keep you and your child from getting HIV. Women in their third trimester should be tested again if they engage in behaviors that put them at risk for HIV. If you are HIV-negative and you have an HIV-positive partner, talk to your doctor about taking pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) to help keep you from getting HIV. Encourage your partner to take ART. People with HIV who take HIV medicine as prescribed and get and keep an undetectable viral load have effectively no risk of transmitting HIV to an HIV-negative partner through sex. If you have HIV, take ART daily as prescribed. If your viral load is not suppressed, your doctor may talk with you about options for delivering the baby that can reduce transmission risk. After birth, babies born to a mother with HIV are given ART right away for 4 to 6 weeks. If you are treated for HIV early in your pregnancy, the risk of transmitting HIV to your baby can be 1% or less. Breast milk can have HIV in it. So, after delivery, you can prevent giving HIV to your baby by not breastfeeding. For more information, see CDC's HIV Among Pregnant Women, Infants, and Children. Content Source: CDC's HIV Basics Date last updated: December 19, 2018 E. Potential Future Options1. HIV VaccineWhat Are Vaccines and What Do They Do?

A vaccine—also called a “shot” or “immunization”—is a substance that teaches your body's immune system to recognize and defend against harmful viruses or bacteria. Vaccines given before you get infected are called “preventive vaccines” or “prophylactic vaccines,” and you get them while you are healthy. This allows your body to set up defenses against those dangers ahead of time. That way, you won't get sick if you're exposed to diseases later. Preventive vaccines are widely used to prevent diseases like polio, chicken pox, measles, mumps, rubella, influenza (flu), hepatitis A and B, and human papillomavirus (HPV). Is There a Vaccine for HIV?No. There is currently no vaccine available that will prevent HIV infection or treat those who have it. Today, more people living with HIV than ever before have access to life-saving treatment with HIV medicines (called antiretroviral therapy or ART), which is good for their health. When people living with HIV achieve and maintain viral suppression by taking medication as prescribed, they can stay healthy for many years and greatly reduce their chance of transmitting HIV to their partners. In addition, others who are at high risk for HIV infection may have access to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), or ART being used to prevent HIV. Yet, unfortunately, in 2015, 39,513 people were diagnosed with HIV infection in the United States, and more than 2.1 million people became newly infected with HIV worldwide. To control and ultimately end HIV globally, we need a powerful array of HIV prevention tools that are widely accessible to all who would benefit from them. Vaccines historically have been the most effective means to prevent and even eradicate infectious diseases. They safely and cost-effectively prevent illness, disability, and death. Like smallpox and polio vaccines, a preventive HIV vaccine could help save millions of lives. Developing safe, effective, and affordable vaccines that can prevent HIV infection in uninfected people is the NIH's highest HIV research priority given its game-changing potential for controlling and ultimately ending the HIV/AIDS pandemic. The long-term goal is to develop a safe and effective vaccine that protects people worldwide from getting infected with HIV. However, even if a vaccine only protects some people who get vaccinated, or even if it provides less than total protection by reducing the risk of infection, it could still have a major impact on the rates of transmission and help control the pandemic, particularly for populations at high risk of HIV infection. A partially effective vaccine could decrease the number of people who get infected with HIV, further reducing the number of people who can pass the virus on to others. By substantially reducing the number of new infections, we can stop the epidemic. For more information, see the video below with Dr. Anthony Fauci, Director of NIH's National Institutes of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID). 2. Long-acting PrEPLong-Acting HIV Prevention Tools

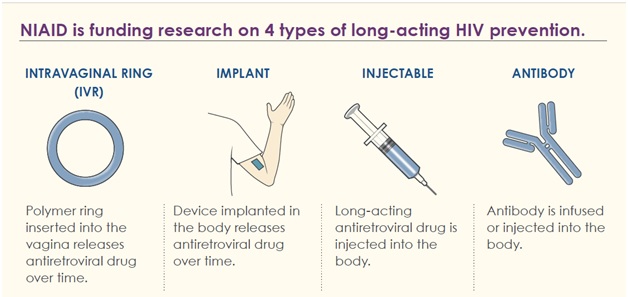

What Are Long-acting HIV Prevention Tools? Long-acting HIV prevention tools are new long-lasting forms of HIV prevention being studied by researchers. These are HIV prevention tools that can be inserted, injected, infused, or implanted in a person's body from once a month to once a year to provide sustained protection from acquiring HIV. These products are not available now, but they might be in the not-too-distant future. Why Are Long-acting HIV Prevention Tools Needed?Currently, people who are HIV-negative but at very high risk for HIV can lower their chances of getting HIV by taking a pill that contains two anti-HIV drugs every day. This is called pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). When taken daily, PrEP can stop HIV from taking hold and spreading throughout your body. PrEP is highly effective when taken daily as prescribed. However, studies have shown that PrEP is much less effective if it is not taken consistently, and that taking a daily pill can be challenging for some people. That's why researchers are working to create new HIV prevention tools that do not require taking a daily pill. Scientists funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) are developing and testing several long-acting forms of HIV prevention that can be inserted, injected, infused, or implanted in a person's body from once a month to once a year. The goal of this research is to provide people with a variety of acceptable, discreet, and convenient choices for highly effective HIV prevention. None of the research on these possible HIV prevention options has been completed, so they are not yet approved by the FDA and are not available for use outside of a clinical trial. What Types of Long-acting HIV Prevention Tools Are Under Study?Four types of long-acting HIV prevention are in design and testing in research studies: intravaginal rings, injectable drugs, implants, and antibodies.  NIH National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases: Long-Acting Forms of HIV Prevention Intravaginal rings for women. Long-acting intravaginal rings are polymer-based products that are inserted into the vagina, where they release release one or more anti-HIV (or antiretroviral) drugs over time. The intravaginal ring at the most advanced stage of research is the dapivirine ring, which was tested in two large clinical trials including the NIH-funded ASPIRE study. The dapivirine ring is undergoing further evaluation in the HOPE open-label extension trial. Injectables. Long-acting injectables are select long-acting antiretroviral drugs that are injected into the body. Injectables are being studied for both HIV prevention and HIV treatment. The first large-scale clinical trial of a long-acting injectable for HIV prevention began in December 2016. Called HPTN 083, the NIH-sponsored study—a partnership with ViiV Healthcare and the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation—is examining whether a long-acting form of the investigational antiretroviral drug cabotegravir, injected once every 8 weeks, can safely protect men and transgender women from HIV infection at least as well as daily PrEP. Results are expected in 2021. A related study called HPTN 084 is testing whether injectable cabotegravir safely prevents HIV infection in young women. Implants. Long-acting implants are small devices that are implanted in the body and release an anti-HIV drug at a controlled rate for continuous protection from HIV over time. NIH is funding the development and testing of several of these implants for HIV prevention. These products have not yet entered clinical trials. Studies supported by other funders are exploring an implant for women that protects users from both HIV and unplanned pregnancy. Antibodies. Scientists have begun to test whether giving people periodic infusions of powerful anti-HIV antibodies can prevent or treat HIV infection. The antibodies involved can stop a wide variety of HIV strains from infecting human cells and thus are described as “broadly neutralizing antibodies” (bNAbs). Two advanced NIH-funded clinical trials are assessing whether giving infusions of bNAbs to healthy men and women at high risk for HIV protects them from acquiring the virus. Several early-stage clinical trials of other bNAbs for HIV prevention also are underway. Can I Use Long-acting HIV Prevention Tools Now?

The more of these actions you take, the safer you will be. To learn more about steps you can take now to prevent getting or transmitting HIV, read other pages in HIV.gov's HIV Prevention section. This page was developed in collaboration with NIH's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Content Source: HIV.gov Date last updated: July 20, 2019 3. Microbicides What Are Microbicides?

Microbicides are experimental products containing drugs that prevent vaginal and/or rectal transmission of HIV and/or sexually transmitted infections. Researchers are studying microbicides delivered in the form of vaginal rings, gels, films, inserts and enemas. A safe, effective, desirable, and affordable microbicide against HIV could help to prevent many new infections. Can Microbicides Prevent HIV Infection? The answer to this question now appears to be “Yes, to a modest degree.” Several large-scale research studies over the past decade have investigated the safety and effectiveness of different microbicides. In 2016, results from the NIH-funded ASPIRE study, a large clinical trial conducted at 15 clinical research sites in Malawi, South Africa, Uganda, and Zimbabwe, showed that a vaginal ring that continuously releases the experimental antiretroviral drug dapivirine provided a modest level of protection against HIV infection in women. The ring reduced the risk of HIV infection by 27 percent in the study population overall and by 61 percent among women ages 25 years and older, who used the ring most consistently. A second clinical trial called The Ring Study conducted in parallel with the ASPIRE study also tested the dapivirine ring for safety and efficacy in women. Similar to ASPIRE, The Ring Study investigators found an overall effectiveness of 31 percent, with a slightly greater reduction in risk of HIV infection among women older than 21 years. To build on the findings from these studies, NIH's National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID) is funding an open-label extension study of the vaginal ring to see if this experimental product can offer increased protection against HIV in an open-label setting in which all participants are counseled on how effective the ring may be, and are invited to use or not use the dapivirine ring in order to yield insight into why some women may choose to use or not to use the ring. Finding HIV prevention options that are acceptable to women and that can be integrated into their daily lives is a critical component of developing prevention strategies that work for diverse populations. Other studies are examining potential rectal microbicide gels to reduce the risk of HIV transmission through anal sex. Some are testing microbicides originally formulated for vaginal use to determine if they are safe, effective, and acceptable when used in the rectum; others focus on the development of products designed specifically for rectal use. Learn more about prior microbicides studies and NIAID's ongoing research on both vaginal and rectal microbicides. Why Are Microbicides Important? The only currently licensed and available biomedical HIV prevention product comes in the form of a daily pill taken orally (tenofovir-emtricitabine sold as Truvada®), and is called pre-exposure prophylaxis, or PrEP. But protection from it requires consistent, daily use. A daily pill can be challenging for some people to take, so other forms of biomedical HIV prevention are being explored. A discreet, long-acting, female-initiated method of prevention such as a microbicide may be a good HIV prevention option for some women. Microbicides may also be preferable to condoms as an HIV prevention option for some women because women would not have to negotiate their use with a partner, as they often must do with condoms. Because women and girls are at particularly high risk for HIV in many parts of the world, it is especially important to have an effective, desirable, woman-initiated HIV prevention tool. Microbicides could make it possible for a woman to protect herself from HIV. In the future, it may be possible to formulate products that combine anti-HIV microbicide agents with contraception. Rectal microbicides would also offer another HIV prevention option for men or women who engage in anal sex. Can You Use a Microbicide to Prevent HIV? Not yet. The ASPIRE study results are promising, but further study is needed, along with approval by drug regulators before the vaginal ring can be used by the public. Meanwhile, research on other formulations and forms of microbicides continues. For now, available forms of protection against sexual transmission of HIV continue to be:

The more of these actions you take, the safer you will be. To learn more, see Lower Your Sexual Risk for HIV. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- QN.No.#12. Viral suppression is when: a) the virus reaches Stage 2, Clinical Latency b) there is a stoppage or reduction of discharge or secretion during sex c) the EVD gets in through broken skin, mucous membranes in the eyes, nose or mouth d) HIV medication reduces the amount of HIV in your blood to a very low level QN.No.#13. Undetectable viral load is: a) when you can stop taking your HIV medication daily because of the negligible levels of the virus b) when your viral load is so low that it doesn't show up in a standard lab test c) a process that usually takes up to 4-5 years of treatment d) usually manifested as elevated free t4 and suppressed TSH is no longer detected [ QN.No.#14. Another (Other) prevention benefit(s) of taking HIV medication to achieve and maintain an undetectable viral load: a) it reduces the risk of mother-to-child transmission from pregnancy, labor, and delivery b) it may reduce HIV transmission risk for people who inject drugs c) you are never required by law to inform your sexual partner that you are HIV positive if you take your medication and you have an undetectable viral load d) a and b [ QN.No.#15. What is PrEP, or pre-exposure prophylaxis? b) is not able to stop HIV from taking hold and spreading throughout the body c) is an HIV prevention method in which the risk of getting HIV from sex reduces by less than 50% d) is not for gay/bisexual men or drug users who share needles or other equipment to inject drugs [ QN.No.#16. What is PEP, or post-exposure prophylaxis? (b) a) is an HIV medication that can be started up to 7 days after exposure to help prevent the HIV virus from taking hold in the body b) is a short course of HIV medicines taken within the first 72 hours after possible exposure to HIV to prevent the virus from taking hold in the body c) is HIV medication meant for regular use by people who may be exposed to HIV frequently d) is not meant for sexual assault victims] [ QN.No.#17. If you are prescribed PEP, you will need to take the HIV medicines every day for ______. a) 7 days b) 28 days c) four to six months d) the rest of your life] [ QN.No.#18. The HIV-negative person can try to protect themselves from HIV by all of the following except: a) use condoms and avoid receptive anal sex b) reduce the number of sexual partners c) take PEP 14 days after a possible HIV exposure d) talk to a doctor about PrEP] [ QN.No.#19. The HIV-positive person can try to prevent transmitting HIV to an HIV-negative partner by all of the following except: a) take HIV medication b) use condoms and get tested and treated for other STD's c) be the insertive partner during anal sex d) never shares needles] |

|

|

HIV / AIDS Course > Chapter 3 - HIV Prevention

Page Last Modified On:

Deprecated: Function strftime() is deprecated in /home/devxspeedy/public_html/lib/smarty-3.1.34/libs/plugins/modifier.date_format.php on line 81 December 30, 2019, 11:20 AM |

|